The Aakhya Weekly #155 | Beyond Bans: The Case for a Smarter State

In Focus: Turning Symbolic Bans into Sustainable Reform

“Let’s just ban it”—in India, that phrase has become a familiar refrain. Whether it’s single-use plastic, e-cigarettes, beef, booze, firecrackers, pornography, or cryptocurrency, banning has become the state’s reflex. And now, most recently, Delhi has added fuel-powered vehicles to the mix. Just days after lifting its previous restrictions, the Delhi government announced that from November 1, 2025, no fuel will be sold to diesel vehicles over 10 years old or petrol vehicles over 15 years old. It’s not an ultimatum on cars per se, but it achieves the same effect, without offering a clear transition path for those impacted. Sometimes this policy posture reflects genuine moral concern or a public health imperative. However, too often, it reveals deeper structural weaknesses: gaps in capacity, enforcement, and institutional imagination.

In this piece, we take the subject seriously, not as trivial symbolic acts, but as policy instruments with high stakes. We ask: when and how should bans be used? When do they work, and when do they backfire? What data remind us of their real costs and limited benefits? Most crucially, how can India transform a blunt instrument into a more precise tool of governance?

The Lure of Moratoriums

Politically, they are a seductive policy tool. They offer swift clarity in moments of uncertainty—exactly what voters tend to approve. When Chandigarh banned plastic bags or Manipur restricted porn, there were headline-grabbing announcements, curated visuals of officials tearing evidence, and immediate media coverage.

However, clarity is not the same as depth. Take plastic. India produces 9.3 million tonnes of plastic waste each year—around 20% of global plastic pollution, of which 85% is mismanaged. Prohibiting certain activities may project control, but without recycling systems or sustainable alternatives, it addresses visibility, not volume.

When it Backfires

Consider India’s repeated reliance on such measures to tackle complex issues. Take the case of single-use plastic. In Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, plastic bans were introduced with political urgency. In Nagpur alone, officials conducted over 168,000 inspections, seized 75 tonnes of plastic, and collected ₹2.68 crore in fines. Yet plastic bags remain widespread. The real cost fell on small vendors and informal workers who lacked affordable alternatives. Rather than eliminating plastic waste, the decision shifted the burden to those least equipped to absorb it, without addressing the deficits in structural waste management.

A similar pattern unfolded in Bihar’s 2016 alcohol prohibition. Framed as a social reform to curb domestic violence and improve public health, the policy led to the seizure of 21 million litres of illicit liquor and nearly 450,000 arrests by 2022. But the underground liquor economy thrived. In December 2022, 73 people died from consuming spurious alcohol. Similar tragedies occurred in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. Instead of curbing harm, it pushed consumption into the shadows, where it became deadlier and harder to monitor.

This logic also extends to digital policy. In 2018, the RBI barred banks from supporting crypto transactions to contain financial risks. However, by the time the Supreme Court overturned the decision in 2020, India had already lost momentum in the global fintech sphere. Developers and startups moved abroad, stalling domestic innovation. The policy move did not mitigate risk—it exported the opportunity instead.

The same tendency was evident in the 2015 pornography ban. Users quickly bypassed restrictions with VPNs, and enforcement fizzled. Yet the attempt sparked a vital debate around digital freedom, censorship, and the absence of sex education. The state’s moral intent did little to reduce access, but it did expose a broader policy vacuum around digital literacy and personal rights.

Across these cases, a common thread emerges: bans often offer the illusion of control but fall short in practice. They displace problems, burden the vulnerable, and avoid investing in the institutional capacity required for real change.

When it Works– and When it Doesn’t

These decisions sound simple, effective, and morally compelling only in theory. They are intended for scenarios where the harm is immediate, undeniable, and non-negotiable—think asbestos, child labour, or hazardous industrial waste. The assumption is that society collectively agrees on the need to eliminate a particular practice, and that the state has the authority and tools to enforce that consensus.

But practice rarely matches theory. Most moratoriums in India are imposed not in contexts of consensus, but in situations of conflict—between economic livelihood and environmental protection, between personal liberty and social morality, between state capacity and public behaviour. It is effective when there are credible alternatives for citizens, reliable infrastructure for implementation, and consistent enforcement across geographies and demographics. When any of these conditions are missing—as they often are—prohibitive measures tend to backfire or eventually die down. India's experience with plastic restrictions and alcohol prohibition shows how intentions, when unsupported by systems, lead to outcomes that are uneven at best and harmful at worst.

Data‑Driven Insights to Measure Impacts

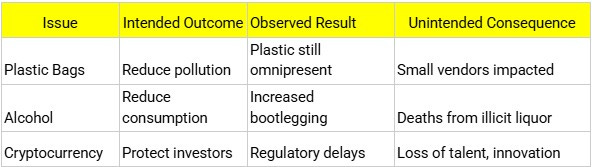

Table 1: Ban Outcomes in India

The data is telling. The imposition of restrictive, haphazard regulations fails precisely because they ignore implementation and equity. They produce dominant symbolic effects, but weak structural ones.

Alternatives and Complements

It is, nevertheless, important to understand that the practice itself need not be eliminated—they have to be repositioned. In many cases, smarter policy alternatives can complement or even replace such measures, leading to more effective and inclusive outcomes. For instance, instead of blocking cryptocurrency outright, India could have introduced a licensing regime for exchanges, enforced KYC norms, and built a regulatory sandbox for innovation. Countries like Singapore and the UK are already pursuing such paths, attempting to balance innovation with accountability.

For plastic, extended producer responsibility (EPR) frameworks are far more sustainable. These models shift the burden of waste collection and recycling to producers and brands, incentivising them to create biodegradable packaging or invest in return logistics. In parallel, behavioural nudges—like campaigns to promote reusable bags or green Diwali celebrations—can gradually shift consumer behaviour. Nudges work better when embargoes feel abrupt; they build habit instead of fear. Moreover, phased implementation is a vital ingredient in successful prohibition. When new and unforeseen restrictive policies are rolled out, they create panic, confusion, and non-compliance. But when introduced in phases—starting with large retailers, followed by institutional users, and eventually reaching small vendors—the chances of compliance and adaptation increase substantially. India’s policy design must move from sweeping commands to layered transitions.

Symbolism vs. Substance

We are witnessing a paradox: bans that look strong but are, in effect, hollow. They are strong in signal, but hollow in change. It becomes a political artefact—a performance that's easy to stage and difficult to sustain.

Comparisons help: shifts in electricity subsidies, digital payment incentives, or Medicaid expansions in other countries reveal how complex policy—with embedded checks, supports, and adaptivity—achieves what a ban never can.

India’s policy reflexes indicate both a hunger for governance and a discomfort with complexity. It is not a failure of intent—often, it is an admission of institutional constraint. Nevertheless, aspiration must be matched by capacity. Prohibitions can serve as a signal, a starting point, or a bridge to deeper reforms. But in themselves, they are insufficient—and often counterproductive. When wielded without evidence, accountability, equity, and support, they are not policy tools—they are policy placeholders.

We need to shift our relationship to the ban, from seeing it as a final statement to treating it as an opening gambit in a longer conversation. It can declare a problem not just identified, but under construction, with citizens, regulators, researchers, and businesses invited to offer solutions together. That’s the India of the future: not one that quick-fixes issues, but one that resolves them with calculated precision. A place where policy stops focusing on what’s banned—and starts focusing on what’s built together.

Top Stories of the Week

India Unveils Vision for $300 Billion Bioeconomy by 2030

At the World Bioproduct Vision Day, Union Minister of Science and Technology Dr. Jitendra Singh unveiled India’s ambitious goal of building a $300 billion bioeconomy by 2030. Emphasising that every Indian is a stakeholder, he called for wider public awareness and inclusive participation in the country's biotechnology mission. The event was organised by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), BIRAC, and iBRIC+, featuring a novel national experiment, the Voices Across the Cities: A Synchronised National Hourly Dialogue Series, which focused on region-specific themes such as marine biomass, agri-residue, forest resources, and industrial valorisation.

Dr. Singh highlighted India’s exponential Biotech growth from just 50 startups a decade ago to nearly 11,000 today, crediting strong policy support and institutional partnerships. He also spoke about the recently launched BioE3 Policy, which integrates environmental sustainability, economic growth, and equity into India's bioeconomy strategy. DBT Secretary and BIRAC Chairman Dr. Rajesh S. Gokhale provided details on the steps to operationalise the policy, including support for pilot manufacturing, regional innovation missions, and bridging research with market needs through collaborations between academia, startups, and industry.

Bihar Reserves 35% Women’s Quota for Local Women

In Bihar, the state government has decided to implement a domicile policy for government jobs reserved for women. Since 2016, a 35% reservation quota has been in place for female candidates in state government jobs. However, the new domicile policy now restricts this quota exclusively to women who are permanent residents of Bihar.

This decision is in response to growing demands for a domicile-based policy in government employment. The move aims to enhance financial independence and job security, specifically for women who are permanent residents of the state.

Additionally, the Cabinet approved the formation of the Bihar Youth Commission. The commission will focus on increasing employment opportunities for local youth, enhancing skill development, and improving the recruitment process for government jobs. It also aims to prioritise local candidates in both the public and private sectors.

A Few Good Reads

Nishant Sahdev warns that AI’s voracious power demands risk overwhelming existing grids and insists that nuclear energy is the sole zero‑carbon source to rely on.

Riya Sinha and Giulia Tercovich suggest that, despite strategic divergences, EU-India collaboration through the Global Gateway initiative could promote transparent and sustainable connectivity in the Indo-Pacific.

Former Ambassador Mohan Kumar highlights that the BRICS Rio Summit Declaration reflects an increasingly assertive Global South, showcasing rare consensus despite geopolitical diversity and the absence of heads of state.

America's Ukraine strategy is faltering, exposing a dangerous mismatch between rhetoric, resources, and public will, suggests Michael Brendan Dougherty.

Pranay Kotasthane contends that China's coercive trade moves against India reflect not strength but anxiety over losing manufacturing dominance.

Changemakers

Maidaan Saaf: A Waste Management Effort at Scale

Maidaan Saaf is a sustainability initiative that aims to improve waste management at large public events in India. It began during the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup 2023 with practical interventions—PET bottle collection, reverse vending machines, and volunteer-led systems—to reduce waste in stadiums.

The approach was later extended to cultural and religious events, including the Rath Yatra, Ganesh Chaturthi, and Mahakumbh 2025. Across these venues, around 4.5 lakh PET bottles were recycled into flags, over 21,000 jackets were made from disposed plastics, and more than 200 tonnes of waste were recovered. At Mahakumbh, the initiative also introduced infrastructure made from recycled materials, including changing rooms, hydration carts, and gear for sanitation workers and boat operators.

The project’s progress and outcomes are now documented here:

https://www.maidaansaaf.com/